There exists today a tiny enclave of Calabrian Greeks, Greek-speaking people in the Aspromonte Mountain region of Reggio Calabria, that seems to have survived millennia…perhaps since the Ancient Greeks began colonizing Southern Italy in the 8th and 7th Centuries BC.

Italian as we know it today was not always spoken throughout Italy. The Italian language did not become the lingua franca until well into the end of the 19th Century during the process of Italian unification, or the Risorgimento.

Until then, the Italian peninsula was made up of Italo-Romance dialects and smaller minority languages that were differentiated by region and historical influences.

Once unification was complete, the Tuscan dialect was ushered into power as the official language of the Italian nation. This became the beginning of the modern Greek language in Calabria, or what is known today as Greko.

There exists today a tiny enclave of Greek-speaking people in the Aspromonte Mountain region of Reggio Calabria that seems to have survived millennia…perhaps since the Ancient Greeks began colonizing Southern Italy in the 8th and 7th Centuries BC.

Their language is called Greko. They survived empires, invasions, ecclesiastical schisms, dictators, nationalistic-inspired assimilation, and much more. Greko is a variety of the Greek language that has been separated from the rest of the Hellenic world for many centuries.

There are various population estimates circulating, but after I visited the region in April 2017 and sat down with several community leaders, the clearest estimate of remaining Greko speakers seems to be between 200 to 300, and numbers continue to decrease.

To help bring more perspective, Greek was the dominant language and ethnic element all throughout what we know today as Calabria, Basilicata, Puglia, and Eastern Sicily until the 14th Century.

Since then, the spread of Italo-Romance languages, along with geographical isolation from other Greek-speaking regions in Italy, caused the language to evolve on its own in Calabria. This resulted in a separate and unique variety of Greek that is different from what is spoken today in Puglia.

The struggle for the survival of Hellenism after antiquity is typically associated with Ottoman occupation in the Eastern Mediterranean, not the Italian peninsula. Few history books I read growing up ever mentioned any type of Greek history or presence in Italy after the glorious era of Magna Graecia. But to dig a little deeper means that we must look at what happened to this ethno-linguistic group after antiquity.

There are many theories or schools of thought regarding the origin of the Greko community in Calabria. Are they descendants of the Ancient Greeks who colonized Southern Italy? Are they remnants of the Byzantine presence in Southern Italy? Did their ancestors come in the 15th to 16th centuries from the Greek communities in the Aegean fleeing Ottoman invasion?

The best answers to all of those questions are yes, yes, and yes. This means that history has shown a continuous Greek presence in Calabria since antiquity. Even though different empires, governments, and invasions occurred in the region, the Greek language and identity seems to have never ceased. Once the glorious days of Magna Graecia were over, there is evidence that shows that Greek continued to be spoken in Southern Italy during the Roman Empire.

Once the Roman Empire split into East (Byzantine) and West, Calabria saw Byzantine rule begin in the 5th Century. This lasted well into the 11th Century and reinforced the Greek language and identity in the region, as well as an affinity to Eastern Christianity.

Today, there is more evidence of a Byzantine legacy rather than an Ancient Greek or Modern Greek footprint.

What’s even more fascinating is that Calabria was apparently a Byzantine monastic hub of sorts. There were over 1,500 Byzantine monasteries in Calabria and people today still remember and adore those saints. Even though Byzantine rule ended in Calabria in the 11th Century, the Greek language continued to be spoken while gradually declining in the region with the spread of Latin and a process of Catholicization.

The modern-day commune of Bova may give some insight into the history of the language in the region. In subsequent centuries after Byzantine rule, Bova became the heart of Greek culture in Calabria, as well as the seat of the Greek church in the region. It is important to note that the liturgical language of the region was Greek until 1572 when Bova was the last in the region to transition to Latin.

Not much is known of what took place between the end of the 16th Century and the Italian Risorgimento in the 19th Century, but there are a couple of details to mention. First, due to multiple invasions and piracy, much of Calabria’s coastal population moved into the mountainous interior.

The isolation and geography of the Greko communities in Calabria definitely worked to the advantage of preserving the language over centuries. We can also possibly conclude that occasional migrations of Greeks to Calabria from the Aegean could have taken place in the 16th and 17th Centuries in response to the Ottoman invasion. There is even evidence that a 17th Century mayor of Bova wrote poems in Greko.

Even though the Greek language had already been in great decline since the departure of the Byzantine Empire in Southern Italy and the spread of Catholicism with Latin liturgy, the language seems to have quietly survived several centuries in the mountains of Calabria.

Once the Risorgimento finally took place, the modern Italian language finally arrived in Calabria at the end of the 19th Century. Like I mentioned before, the Italian language that arrived was essentially the Tuscan dialect that was chosen as the national language.

Due to the complexities of the Risorgimento and the new multifaceted Italian state (Northern Italy vs. Southern Italy), a mindset was ushered into Calabria and the surrounding Southern Italian regions. This deeply affected the Greko community and language.

The shame and embarrassment of speaking Greko began in the 20th Century and it intensified during the Fascist movement.

It became greatly frowned upon to speak Greko during that time. The nickname paddeki, meaning stupid, was commonly given to Greko speakers for speaking their mother tongue. Assimilation into Italian culture and the rejection of the Greko language seemed like the best option for many Greko speakers, especially for Greko parents wanting to give their children a promising future.

To get a solid grasp on the current status of the Greko language in Calabria, I visited the homes of some local Greko families in Bova Marina, Condofuri Marina, Galliciano, and Bova.

With only 200 to 300 Greko speakers remaining today, the vast majority of them are elderly. We were able to sit down with Salvatore Siviglia (Roghudi Nuovo), Domenico Nucera Milinari (Condofuri Marina), Mimmo Nucera (Gallicianò), and Pietro Romeo (Bova).

Hearing the stories and experiences from each of these individuals gave me a good backdrop of what life was like for the Greko community in Calabria, especially before the 1960s. Many of them claimed that only the older generations continue to speak Greko today, which seemed to be quite evident during my trip.

We sat down with Salvatore Siviglia in his current home in Roghudi Nuovo, and he explained to us what life was like in his hometown of Roghudi (Side Note: Salvatore, along with all of the residents of Roghudi, were forced to relocate to Roghudi Nuovo in the 1980s due to severe flooding).

“Until the 1960s, there were no roads, electricity, or plumbing to most of the Greko villages,” Salvatore recalled. “When the schools arrived, Italian was the taught language and Greko was learned at home. There was no government assistance back then for the Greko language. People in Rome (referring to the Italian government) did not care about our language.”

The Italian government did not pay much attention to the Greko language and did not help preserve it because its speakers did not pose a threat of secession or independence much like the Northern Italian minorities or the Basques and Catalans of Spain.

Assistance from Greece

In the last twenty to thirty years, there have been efforts made in conjunction with the Greek government to bring education and revitalization to the Greko language and culture in Calabria. This activity has definitely brought more cultural awareness to locals but unfortunately has not had a positive effect on the language.

Unlike Modern Greek, the Greko language is written with Latin script. This in itself creates a clear barrier between the local Greko population of Calabria and the incoming teachers from Greece who brought the modern Greek language using the Greek alphabet. Perhaps the efforts from the Greek government and Greek organizations were intended to connect the Greko community of Calabria to a variety of Greek (Modern Greek) that was more sustainable in the 21st Century.

There are many factors that have led to the current status of the Greko language, which remains in severe decline and near extinction.

Although only a few hundred speakers remain, there seem to be thousands in the region that have a Greko ethnic identity but have no knowledge of the language.

I observed how passionate and hardworking some Greko people were in regards to the survival of their dying language. It was deeply moving and encouraging. In essence, they are guardians of Hellenism in this small region tucked away in the toe of the Italian peninsula.

Below are a list of the current population centers today that have Greko-speaking residents as well as settlements that at one time had Greko speakers in the past 100 years. Keep in mind that several settlements in the mountainous interior experienced population shifts in the last several decades. I have attempted to give background details about each settlement listed.

Greko-Speaking Settlements Today:

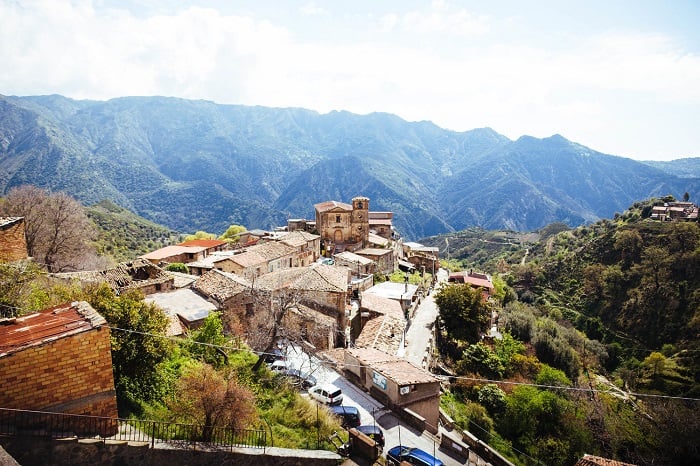

Galliciano: The only remaining original Greko-speaking settlement in the mountains, locals have not been forced to move or resettle on the coast like other surrounding mountain settlements.

Roghudi Nuovo: Established in the 1980s after the original settlement of Roghudi in the mountainous interior was threatened by severe flooding, and all of its residents were consequently relocated to Roghudi Nuovo, meaning New Roghudi.

Bova Marina: Bova Marina is the coastal settlement of its corresponding mountainous settlement, Bova (sometimes called Bova Superiore). Many of Bova’s residents have relocated to Bova Marina over the last decades in search of better economic opportunities and exposure to commerce on the coast.

Melito di Porto Salvo

Reggio di Calabria: The largest city in Calabria, Reggio has a few neighborhoods where Greko-speaking people have relocated over the decades.

Roghudi: Nestled in the Aspromonte Mountains, Roghudi’s residents were forced to relocate closer to the coast after severe flooding took place in the 1980s. The new settlement would be named Roghudi Nuovo.

Bova: Once the epicenter of Greek culture and religion in the region, Bova has no indigenous Greko speakers remaining today. Many of its former Greko-speaking inhabitants have moved to its coastal settlement of Bova Marina in the last thirty to forty years for economic opportunity.

Important side note: Greko vs. Griko: The two are not to be confused. The variation of Greek that is spoken in Calabria (Greko) is different from the variety of Greek spoken in Puglia, known as Griko.

John Kazaklis, http://istoria.life / Greek Reporter

Photo: Gallicianò, Calabria: The only remaining original Greko-speaking settlement in the Aspromonte Mountains. Locals have not been forced to move or resettle on the coast like other Greko settlements. Credit: John Kazaklis

Εστάλη στην ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ, 27/5/2024 #ODUSSEIA #ODYSSEIA, Greek reporter