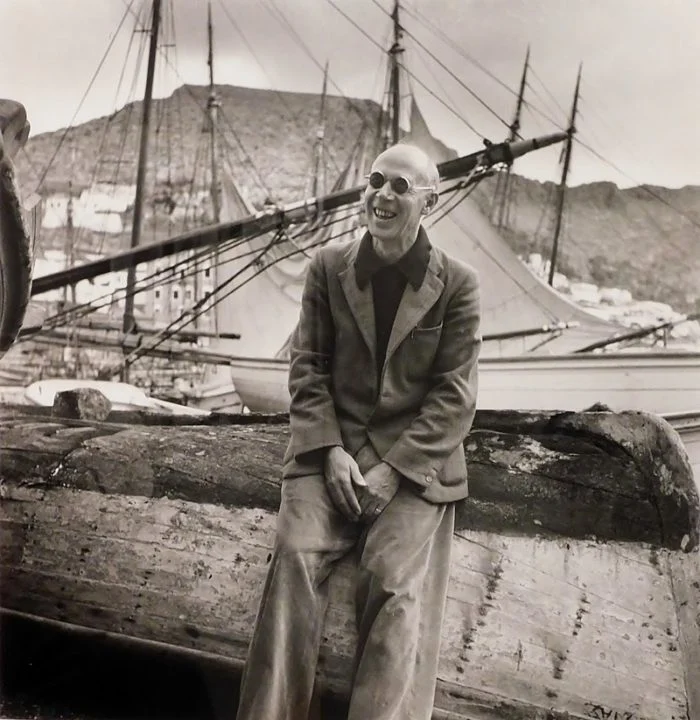

Henry Miller, the author of Tropic of Cancer and one of the greatest American writers, was enamored with Greece, and his favorite, self-authored book was a travelogue of the country he loved.

The Colossus of Maroussi is an impressionist travel book written in 1939 that reads like an ode to Greece and the time the author spent there.

Miller, who lived from 1891 to 1980, was an unconventional writer in every way. He traveled abroad extensively, trying to live outside the restraints of the conservative American society of the 1920s to 1930s.

The American writer’s work is full of reflections on society, philosophical inquiry, embellished autobiographical facts, impressionistic meanderings, and graphic descriptions of sex, which was, at that time, a taboo topic in literature in the United States.

Grecian Delight supports Greece

In 1939, he was invited to Greece by his friend, Lawrence Durrell, the well-known British writer, so he travelled to the Mediterranean country to rejuvenate himself.

The nine months he spent in “the home of the gods,” as he describes Greece, were an inspiration, and he considered the book he wrote there to be his greatest literary accomplishment.

A restless spirit, Miller moved to Paris in the 1930s. The French capital was nothing like the conservative United States he left behind.

There, he wrote his first two novels, Tropic of Cancer (1934) and Tropic of Capricorn (1939), both including sex scenes that made American publishers refuse to publish them.

The books that were found to be completely obscene in the 1930s, were finally published in 1961. By then, Miller’s literary genius had received the recognition deserved.

Durrell was living with his family on the island of Corfu in Greece when he invited Miller to join him there. The American writer discovered what he referred to as the “home of the gods” in the nine months he spent there.

“Greece is the home of the gods; they may have died but their presence still makes itself felt. The gods were of human proportion: they were created out of the human spirit,” he wrote.

Accompanied by his British friend, Miller traveled extensively in Greece. He visited Athens, Epidaurus, Mycenae, sailed to Crete and Hydra, and traveled to other parts of the country, feeding his soul.

If life in cosmopolitan, carefree pre-war Paris was an inspiration for the American writer, rural Greece was his touchstone with nature, a world full of earthy wonders previously unknown to him.

“The light of Greece opened my eyes, penetrated my pores, extended to my whole being. I went back to the world having found the true center and the true meaning of cosmic rotation,” Miller wrote.

In The Colossus of Maroussi, Miller wrote about his Greek adventures with Durrell in impressionistic style.

He wrote about almost being trampled by a herd of sheep while laying naked on a beach, drinking cool water from sacred springs, and sleeping in hotels full of the past and mildew.

Upon his visit to Epidaurus and the ancient theater, the American writer marveled: “I never knew the meaning of peace, until I arrived at Epidaurus…I am talking of course of the peace that passeth all understanding. There is no other kind.”

But among his epiphanies in Greece and his many adventures, his meeting with the true Colossus of Maroussi, the main theme of Miller’s book on Greece, was his inspiration.

The man that was the inspiration for the title of Henry Miller’s book about Greece was none other than Giorgos (George) Katsimbalis (1899-1978).

A larger than life character, Katsimbalis was an intellectual, writer, and editor of modern Greek literature bibliography.

Being friends with Durrell, the British writer introduced Katsimbalis to Miller, and the two men hit it off instantly.

Katsimbalis “could galvanize the dead with his talk,” Miller said about his new Greek friend admiringly.

Soon enough, a circle of artists, poets, and writers formed around Miller, Katsimbalis, and Durrell. The intellectual company was joined by Nobel laureate poet Giorgos Seferis and the renowned painter, sculptor, and writer Nikos Hatzikyriakos Ghikas.

Yet, the protagonist in the book is the Colossus Katsimbalis although some critics say that the book is a self-portrait of Miller himself on a journey of a lifetime in an unforgettable place.

Miller writes in The Colossus of Maroussi:

Marvelous things happen to one in Greece—marvelous good things which can happen to one nowhere else on earth. Somehow, almost as if He were nodding, Greece still remains under the protection of the Creator. Men may go about their puny, ineffectual bedevilment, even in Greece, but God’s magic is still at work[,] and…no matter what the race of man may do or try to do, Greece is still a sacred precinct—and my belief is it will remain so until the end of time.

The last lines of The Colossus of Maroussi read like both a declaration and an admonition:

Greece herself may become embroiled as we ourselves are now becoming embroiled, but I refuse categorically to become anything less than the citizen of the world which I silently declared myself to be when I stood in Agamemnon’s tomb. From that day forth[,] my life was dedicated to the recovery of the divinity of man. Peace to all men, I say, and life more abundant!

After his life-changing journey to Greece, Miller returned to the United States. The Colossus of Maroussi was published in 1941. It was his third book and his favorite.

Miller had left Greece, but he still carried it inside him:

Greece had done something for me which New York, nay, even America itself, could never destroy. Greece has made me free and whole…To those who think that Greece to-day is of no importance[,] let me say that no greater error could be committed.

In 1954, the “Colossus,” Giorgos Katsimbalis, traveled to the United States under the Smith-Mundt Act and stayed at Miller’s house in Big Sur, California.

Katsimbalis loved the area, later writing “I stayed at his place for two days. It’s a dream place. I will be forever grateful to him for allowing me to see one of the best corners of the world.”

Philip Chrysopoulos

Εστάλη στην ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ, 21/6/2024 #ODUSSEIA #ODYSSEIA, Greek Reporter